Tokyo, Japan – Yu Takagi could not believe his eyes. Sitting alone at his desk on a Saturday afternoon in September, he watched in awe as artificial intelligence decoded a subject’s brain activity to create images of what he was seeing on a screen.

“I still remember when I saw the first [AI-generated] images,” Takagi, a 34-year-old neuroscientist and assistant professor at Osaka University, told Al Jazeera.

“I went into the bathroom and looked at myself in the mirror and saw my face, and thought, ‘Okay, that’s normal. Maybe I’m not going crazy’”.

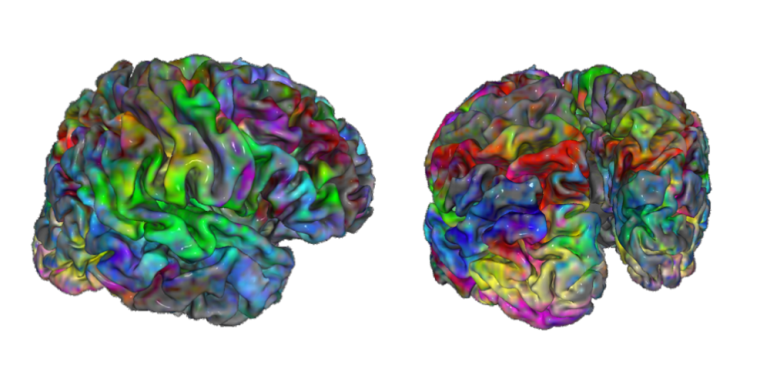

Takagi and his team used Stable Diffusion (SD), a deep learning AI model developed in Germany in 2022, to analyze the brain scans of test subjects shown up to 10,000 images while inside an MRI machine.

After Takagi and his research partner Shinji Nishimoto built a simple model to “translate” brain activity into a readable format, Stable Diffusion was able to generate high-fidelity images that bore an uncanny resemblance to the originals.

The AI could do this despite not being shown the pictures in advance or trained in any way to manufacture the results.

“We really didn’t expect this kind of result,” Takagi said.

Takagi stressed that the breakthrough does not, at this point, represent mind-reading – the AI can only produce images a person has viewed.

“This is not mind-reading,” Takagi said. “Unfortunately there are many misunderstandings with our research.”

“We can’t decode imaginations or dreams; we think this is too optimistic. But, of course, there is potential in the future.”

But the development has still raised concerns about how such technology could be used in the future amid a broader debate about the risks posed by AI in general.

In an open letter last month, tech leaders including Tesla founder Elon Musk and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak called for a pause on the development of AI due to “profound risks to society and humanity.”

Despite his excitement, Takagi admits that fears around mind-reading technology are not without merit, given the possibility of misuse by those with malicious intent or without consent.

“For us, privacy issues are the most important thing. If a government or institution can read people’s minds, it’s a very sensitive issue,” Takagi said. “There needs to be high-level discussions to make sure this can’t happen.”

Takagi and Nishimoto’s research generated much buzz in the tech community, which has been electrified by breakneck advancements in AI, including the release of ChatGPT, which produces human-like speech in response to a user’s prompts.

Their paper detailing the findings ranks in the top 1 percent for engagement among the more than 23 million research outputs tracked to date, according to Altmetric, a data company.

The study has also been accepted to the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), set for June 2023, a common route for legitimizing significant breakthroughs in neuroscience.

Even so, Takagi and Nishimoto are cautious about getting carried away about their findings.

Takagi maintains that there are two primary bottlenecks to genuine mind reading: brain-scanning technology and AI itself.

Despite advancements in neural interfaces – including Electroencephalography (EEG) brain computers, which detect brain waves via electrodes connected to a subject’s head, and fMRI, which measures brain activity by detecting changes associated with blood flow – scientists believe we could be decades away from being able to accurately and reliably decode imagined visual experiences.

In Takagi and Nishimoto’s research, subjects had to sit in an fMRI scanner for up to 40 hours, which was costly as well as time-consuming.

In a 2021 paper, researchers at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology noted that conventional neural interfaces “lack chronic recording stability” due to the soft and complex nature of neural tissue, which reacts in unusual ways when brought into contact with synthetic interfaces.

Furthermore, the researchers wrote, “Current recording techniques generally rely on electrical pathways to transfer the signal, which is susceptible to electrical noises from surroundings. Because the electrical noise significantly disturbs the sensitivity, achieving fine signals from the target region with high sensitivity is not yet an easy feat.”

Current AI limitations present a second bottleneck, although Takagi acknowledges these capabilities are advancing by the day.

“I’m optimistic for AI but I’m not optimistic for brain technology,” Takagi said. “I think this is the consensus among neuroscientists.”

Takagi and Nishimoto’s framework could be used with brain-scanning devices other than MRI, such as EEG or hyper-invasive technologies like the brain-computer implants being developed by Elon Musk’s Neuralink.

Even so, Takagi believes there is currently little practical application for his AI experiments.

For a start, the method cannot yet be transferred to novel subjects. Because the shape of the brain differs between individuals, you cannot directly apply a model created for one person to another.

But Takagi sees a future where it could be used for clinical, communication or even entertainment purposes.

“It’s hard to predict what a successful clinical application might be at this stage, as it is still very exploratory research,” Ricardo Silva, a professor of computational neuroscience at University College London and research fellow at the Alan Turing Institute, told Al Jazeera.

“This may turn out to be one extra way of developing a marker for Alzheimer’s detection and progression evaluation by assessing in which way one could spot persistent anomalies in images of visual navigation tasks reconstructed from a patient’s brain activity.”

Silva shares concerns about the ethics of technology that could one day be used for genuine mind reading.

“The most pressing issue is to what extent the data collector should be forced to disclose in full detail the uses of the data collected,” he said.

“It’s one thing to sign up as a way of taking a snapshot of your younger self for, maybe, future clinical use… It’s yet another completely different thing to have it used in secondary tasks such as marketing, or worse, used in legal cases against someone’s own interests.”

Still, Takagi and his partner have no intention of slowing down their research. They are already planning version two of their project, which will focus on improving the technology and applying it to other modalities.

“We are now developing a much better [image] reconstructing technique,” Takagi said. “And it’s happening at a very rapid pace.”