Pocket gadgets were all the rage in Adam Smith’s day. Their popularity inspired one of the most paradoxical, charming and insightful passages in his work.

The best known are watches. A pocket timepiece was an 18th century man’s must-have fashion accessory, its presence indicated by a ribbon or bright steel chain hanging from the owner’s waist, bedecked with seals and a watch key. Contemporary art depicts not just affluent people but sailors and farm workers sporting watch chains. One sailor even wears two. “It had been the pride of my life, ever since pride commenced, to wear a watch,” wrote a journeyman stocking maker about acquiring his first in 1747.

Laborers could buy secondhand watches and pawn them when they needed cash. A favorite target for pickpockets, “watches were consistently the most valuable item of apparel stolen from working men in the eighteenth century,” wrote historian John Styles, who analyzed records from several English jurisdictions.

But timepieces were hardly the only gizmos stuffing 18th century pockets, especially among the well-to-do. At a coffeehouse, a gentleman might pull out a silver nutmeg grater to add spice to his drink or a pocket globe to make a geographical point. The scientifically inclined might carry a simple microscope, known as a flea glass, to examine flowers and insects while strolling through gardens or fields. He could gaze through a pocket telescope and then, with a few twists, convert it into a mini-microscope. He could improve his observations with a pocket tripod or camera obscura and could pencil notes in a pocket diary or on an erasable sheet of ivory. (Not content with a single sheet, Thomas Jefferson carried ivory pocket notebooks.)

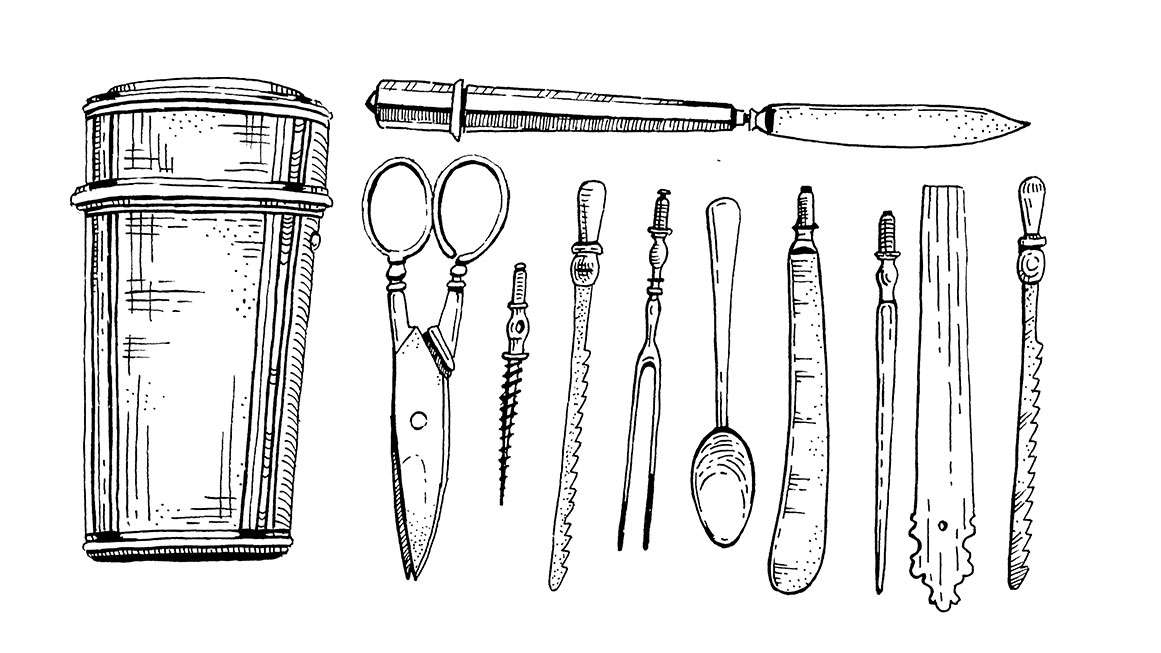

The coolest of all pocket gadgets were what antiquarians call ethical and Smith referred to as “tweezer cases.” A typical 18th century etui looks like a slightly oversized cigarette lighter covered in shagreen, a textured rawhide made from shark or ray skin. The lid opens up to reveal an assortment of miniature tools, each fitting into an appropriately shaped slot. Today’s crossword puzzle clues often describe etuis as sewing or needle cases, but that was only one of many varieties. An etui might contain drawing instruments—a compass, ruler, pencil, and set of pen nibs. It could hold surgeon’s tools or tiny perfume bottles. Many offered a handy tool set for travelers: a tiny knife, two-pronged fork, and snuff spoon; scissors, tweezers, a razor, and an earwax scraper; a pencil holder and pen nib; perhaps a ruler or bodkin. The cap of a cylindrical etui might separate into a spyglass.

All these “toys,” as they were called, kept busy early manufacturers, especially in the British metal-working capital of Birmingham. A 1767 directory listed some 100 Birmingham toy makers, producing everything from buttons and buckles to tweezers and toothpick cases. “For Cheapness, Beauty and Elegance no Place in the world can vie with them,” the directory declared. Like Smith’s famous pin factory, these preindustrial plants depended on hand tools and the division of labor, not automated machinery.

Ingenious and ostensibly useful, pocket gadgets and other toys epitomized a new culture of consumption that also included tea, tobacco, gin, and printed cotton fabrics. These items were neither the traditional indulgences of the rich nor the necessities of life. Few people need a pocket watch, let alone a flea glass or an etui. But these gadgets were fashionable, and they tempted buyers from a wide range of incomes.

A fool “cannot withstand the charms of a toyshop; snuff-boxes, watches, heads of canes, etc., are his destruction,” the Earl of Chesterfield warned his son in a 1749 letter. He returned to the subject the following year. “There is another sort of expense that I will not allow, only because it is a silly one,” he wrote. “I mean the fooling away your money in baubles at toy shops. Have one handsome snuff-box (if you take snuff), and one handsome sword; but then no more pretty and very useless things.” A fortune, Chesterfield cautioned, could quickly disappear through impulse purchases.

in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, first published in 1759, Smith examined what made these objects so enticing. Pocket gadgets claimed to have practical functions, but these “trinkets of frivolous utility” struck Smith as more trouble than they were worth. He deemed their appeal less practical than aesthetic and imaginative.

“What pleases these lovers of toys is not so much the utility,” Smith wrote, “as the aptness of the machines which are fitted to promote it. All their pockets are stuffed with little conveniences. They contrive new pockets, unknown in the clothes of other people, in order to carry a greater number.” Toys embodied aptness, “the beauty of order, of art and contrivance.” They were ingenious and precise. They were cool. And they weren’t the only objects of desire with these qualities.

The same pattern applied, Smith argued, to the idea of wealth. He portrayed the ambitious son of a poor man, who imagined that servants, coaches, and a large mansion would make his life run smoothly. Pursuing a glamorous vision of wealth and convenience, he experiences anxiety, hardship and fatigue. Finally, in old age, “he begins at last to find that wealth and greatness are their trinkets of frivolous utility, no more adapted for procuring the ease of body or tranquillity of mind than the tweezer-cases of the lover of toys.”

Yet Smith didn’t condemn the aspiring poor man or deride the lover of toys. He depicted them with sympathetic bemusement, recognizing their foibles as both common and paradoxically productive. We evaluate such desires as irrational only when we’re sick or depressed, he suggested. In a good mood, we care less about the practical costs and benefits than about the joys provided by “the order, the regular and harmonious movement of the system….The pleasures of wealth and greatness, when considered in this complex view, strike the imagination as something grand and beautiful and noble, of which the attainment is well worth all the toil and anxiety.”

Besides, Smith suggested, pursuing the false promise of tranquility and convenience had social benefits. It was nothing less than the source of civilization itself: “It is this which first prompted them to cultivate the land, to build houses, to found cities and commonwealths, and to invent and improve all the sciences and arts, which ennoble and embellish human beings life; which has entirely changed the whole face of the globe, has turned the rude forests of nature into agreeable and fertile plains, and made the trackless and barren ocean a new fund of subsistence, and the great high road of communication to the different nations of the earth.”

Then Smith gave his analysis a twist. The same aesthetic impulse that draws people to ingenious trinkets and leads them to pursue wealth and greatness, he argues, also inspires projects for public improvements, from roads and canals to constitutional reforms. However worthwhile one’s preferred policy might be for public welfare, their benefits—like those of a pocket globe—are secondary to the beauty of the system.

“The perfection of police, the extension of trade and manufactures, are noble and magnificent objects,” he wrote. “The contemplation of them pleases us, and we are interested in whatever can tend to advance them. They make part of the great system of government, and the wheels of the political machine seem to move with more harmony and ease with their means. We take pleasure in holding the perfection of a system so beautiful and grand, and we are uneasy until we remove any obstruction that can at least disturb or encumber the regularity of its motions.” Only the least self-aware policy will fail to see the truth in Smith’s claim.

Here, however, the separation of means and ends can be more serious than in the case of a trinket of frivolous utility. Buying a gadget you don’t need because you like the way it works doesn’t hurt anyone but you. Enacting policies because they sound cool can hurt the public they’re supposed to benefit. “All constitutions of government,” Smith reminded readers, “are valued only in proportion as they tend to promote the happiness of those who live under them. This is their sole use and end.” Elsewhere in The Theory of Moral SentimentsSmith criticized the “man of the system” who imposed his ideal order, heedless of the wishes of those he governed.

Smith appreciated the beauty and allure of systems. His life’s work was to formulate systematic understandings of social orders, and he concluded his discussion on an optimistic note. Depicting an appealingly complicated system, he suggested, could enlist those otherwise uninterested in beneficial reforms. Seduce them with organization charts!

“You will be more likely to persuade,” Smith wrote, “if you describe the great system of public police which procures these advantages, if you explain the connexions and dependencies of its several parts, their mutual subordination to one another, and their general subserviency to the happiness of the society; if you show how this system might be introduced into his own country, what it is that hinders it from taking place there at present, how those obstructions might be removed, and all the several wheels of the machine of government be made to move with more harmony and smoothness, without grating upon one another, or mutually retarding one another’s motions.”

It’s hard not to see this argument as the inspiration for Wealth of Nations. If Smith could make an economy of free exchange seem as cool as the latest intricate gadget, he might just be able to sell it.